# Install and load the igraph package

install.packages("igraph")

library(igraph)

# Example: Load an edge list from CSV

edge_list <- read.csv("data/friendship_edges.csv")

# Create the graph object (directed network)

g <- graph_from_data_frame(edge_list, directed = TRUE)

# Plot the network

plot(g, main = "Friendship Network")Section 4 Social Network Analyses (Relational Data)

4.1 Overview

Social network analysis (SNA) is the process of investigating social structures through the use of networks and graph theory. It is a technique used to map and measure relationships and flows between people, groups, organizations, computers, or other information/knowledge processing entities. SNA can be a useful tool for understanding the team structures, for example, in an online classroom. It can be an additional layer of understanding the outcomes (or predictors) of certain instructional interventions. Used this way SNA can be used to identify patterns and trends in social networks, as well as to understand how these networks operate. Additionally, SNA can be used to predict future behavior in social networks, and to design interventions that aim to improve the functioning of these networks.

4.2 Accessing SNA Data

Social Network Analysis (SNA) relies on relational data—information about connections (edges) between entities (nodes) such as students, teachers, or organizations. Compared to traditional survey or tabular data, SNA requires pairwise relational information. In education, this could include “who collaborates with whom,” “who talks to whom,” or digital traces of discussion and collaboration in online platforms.

4.2.1 Types and Sources of SNA Data

There are several common sources and structures for SNA data in educational and social science contexts:

- Survey-based Network Data: Collected via roster or name generator questions, e.g., “List the classmates you discuss assignments with.”

- Behavioral/Observational Data: Derived from logs of actual interactions, e.g., forum replies, emails, classroom seating.

- Archival or Digital Trace Data: Extracted from digital platforms such as MOOCs, LMS discussion forums, Slack, Twitter, or Facebook.

- Administrative/Organizational Data: Information about formal structures such as team membership or co-authorship.

Data Structure: Most SNA data are formatted as: - Edge List (two columns: source and target) - Adjacency Matrix (rows and columns are actors; cell values indicate a tie) - Node Attributes (supplementary information about each node, e.g., gender, role)

4.2.2 Example 1: Creating a Simple Network from an Edge List

Below is an example of constructing a network from a simple CSV edge list. This mirrors typical classroom survey data (“who do you consider your friend in this class?”).

4.2.3 Example 2: Generating Network Data from Digital Traces

Many educational datasets now come from online discussion forums, MOOCs, or LMS systems. For example, the MOOC case study (Kellogg & Edelmann, 2015) uses reply relationships in online courses to construct discussion networks.

# Suppose you have a data frame with columns: from_user, to_user

mooc_edges <- read.csv("data/mooc_discussion_edges.csv")

g_mooc <- graph_from_data_frame(mooc_edges, directed = TRUE)

plot(g_mooc, main = "MOOC Discussion Network")4.2.4 Example 3: Collecting SNA Data via Surveys

If you want to collect your own network data:

Ask participants to name or select (from a roster) their friends, collaborators, or contacts.

Compile responses into an edge list.

Example survey prompt:

“Please list up to five classmates you seek help from most frequently.”

Tip:

Survey-based SNA is easier to manage with small to medium groups. For larger networks, digital trace or archival data may be more practical.

4.2.5 Node Attribute Data

You can also load additional data about each node (student, teacher, etc.) to enable richer analyses (e.g., centrality by gender or role).

node_attributes <- read.csv("data/friendship_nodes.csv")

# Add attributes to igraph object

V(g)$gender <- node_attributes$gender[match(V(g)$name, node_attributes$name)]4.2.6 Further Examples

- Public Datasets:

- Synthetic Data:

R’s

igraphpackage can also generate sample networks for practice:g_sample <- sample_gnp(n = 10, p = 0.3) plot(g_sample, main = "Random Sample Network")

4.2.7 Best Practices and Tips

- Ethics: Social network data can be sensitive. Protect anonymity and comply with IRB/data use guidelines.

- Format Consistency: Always clarify whether ties are directed/undirected, binary/weighted, and ensure consistent formatting.

- Missing Data: Especially in survey-based SNA, missing responses can impact network structure and interpretation.

4.2.8 Summary

Accessing SNA data involves both careful design (in the case of surveys/observations) and extraction/wrangling (in the case of digital traces or archival records). The choice of data source and structure will directly influence the kinds of questions you can answer with SNA.

Recommended Reading:

- Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Johnson, J. C. (2018). Analyzing Social Networks (2nd ed). SAGE.

- Kellogg, S., & Edelmann, A. (2015). Massive open online course discussion forums as networks.

4.4 Case Study: Hashtag Common Core

4.4.1 Purpose & Case

The purpose of this case study is to demonstrate the application of social network analysis (SNA) in a real-world policy context: the heated national debate over the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) as it played out on Twitter. Drawing on the work of Supovitz, Daly, del Fresno, and Kolouch, the #COMMONCORE Project provides a vivid example of how social media-enabled networks shape educational discourse and policy.

This case focuses on: - Identifying key actors (“transmitters,” “transceivers,” and “transcenders”) and measuring their influence, - Detecting subgroups/factions within the conversation, - Exploring how sentiment about the Common Core varies across network positions, - Demonstrating network wrangling, visualization, and analysis using real tweet data.

Data Source

Data was collected from Twitter’s public API using keywords/hashtags related to the Common Core (e.g., #commoncore, ccss, stopcommoncore). The dataset includes user names, tweets, mentions, retweets, and relevant timestamps from a sample week. Only public tweets are included, and user privacy is respected.

4.4.2 Sample Research Questions

- RQ1: Who are the “transmitters,” “transceivers,” and “transcenders” in the Common Core Twitter network?

- RQ2: What subgroups or factions exist within the network, and how are they structured?

- RQ3: How does sentiment about the Common Core vary across actors and subgroups?

- RQ4: What other patterns of communication (e.g., centrality, clique formation, isolates) characterize this network?

4.4.3 Analysis

Step 1: Load Required Packages

library(tidyverse)

library(tidygraph)

library(ggraph)

library(skimr)

library(igraph)

library(tidytext)

library(vader)Step 2: Data Import and Wrangling

# Import tweet data (edgelist format: sender, receiver, timestamp, text)

ccss_tweets <- read_csv("data/ccss-tweets.csv")

# Prepare the edgelist (extract sender, mentioned users, and tweet text)

ties_1 <- ccss_tweets %>%

relocate(sender = screen_name, target = mentions_screen_name) %>%

select(sender, target, created_at, text)

# Unnest receiver to handle multiple mentions per tweet

ties_2 <- ties_1 %>%

unnest_tokens(input = target,

output = receiver,

to_lower = FALSE) %>%

relocate(sender, receiver)

# Remove tweets without mentions to focus on direct connections

ties <- ties_2 %>%

drop_na(receiver)

# Save for reproducibility

write_csv(ties, "data/ccss-edgelist.csv")

# Build nodelist

actors_1 <- ties %>%

select(sender, receiver) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = c(sender,receiver))

actors <- actors_1 %>%

select(value) %>%

rename(actors = value) %>%

distinct()

write_csv(actors, "data/ccss-nodelist.csv")Step 3: Create Network Object

ccss_network <- tbl_graph(edges = ties,

nodes = actors,

directed = TRUE)

ccss_network# A tbl_graph: 46 nodes and 42 edges

#

# A directed multigraph with 14 components

#

# Node Data: 46 × 1 (active)

actors

<chr>

1 DistanceLrnBot

2 k12movieguides

3 WEquilSchool

4 JoeWEquil

5 SumayLu

6 fluttbot

7 BodShameless

8 Math

9 ozsultan

10 sfchronicle

# ℹ 36 more rows

#

# Edge Data: 42 × 4

from to created_at text

<int> <int> <dttm> <chr>

1 1 2 2021-06-28 09:53:54 "#Luca Movie Guide | Worksheet | Questions | …

2 3 4 2021-06-28 02:32:59 "Why public schools should focus more on buil…

3 3 3 2021-06-28 02:32:59 "Why public schools should focus more on buil…

# ℹ 39 more rowsStep 4: Network Structure – Components, Cliques, and Communities

- Components

- Identify weak and strong components (connected subgroups):

ccss_network <- ccss_network |>

activate(nodes) |>

mutate(weak_component = group_components(type = "weak"),

strong_component = group_components(type = "strong"))

# View component sizes

ccss_network |>

as_tibble() |>

group_by(weak_component) |>

summarise(size = n()) |>

arrange(desc(size))# A tibble: 14 × 2

weak_component size

<int> <int>

1 1 14

2 2 6

3 3 4

4 4 3

5 5 3

6 6 2

7 7 2

8 8 2

9 9 2

10 10 2

11 11 2

12 12 2

13 13 1

14 14 1- Cliques

- Identify fully connected subgroups (if any):

clique_num(ccss_network)[1] 4 cliques(ccss_network, min = 3)[[1]]

+ 3/46 vertices, from 7825daf:

[1] 4 5 6

[[2]]

+ 3/46 vertices, from 7825daf:

[1] 39 40 41

[[3]]

+ 3/46 vertices, from 7825daf:

[1] 3 4 6

[[4]]

+ 4/46 vertices, from 7825daf:

[1] 3 4 5 6

[[5]]

+ 3/46 vertices, from 7825daf:

[1] 3 4 5

[[6]]

+ 3/46 vertices, from 7825daf:

[1] 3 5 6- Communities

- Detect densely connected communities using edge betweenness:

ccss_network <- ccss_network |>

morph(to_undirected) |>

activate(nodes) |>

mutate(sub_group = group_edge_betweenness()) |>

unmorph()

ccss_network |>

as_tibble() |>

group_by(sub_group) |>

summarise(size = n()) |>

arrange(desc(size))# A tibble: 16 × 2

sub_group size

<int> <int>

1 1 10

2 2 6

3 3 4

4 4 3

5 5 3

6 6 2

7 7 2

8 8 2

9 9 2

10 10 2

11 11 2

12 12 2

13 13 2

14 14 2

15 15 1

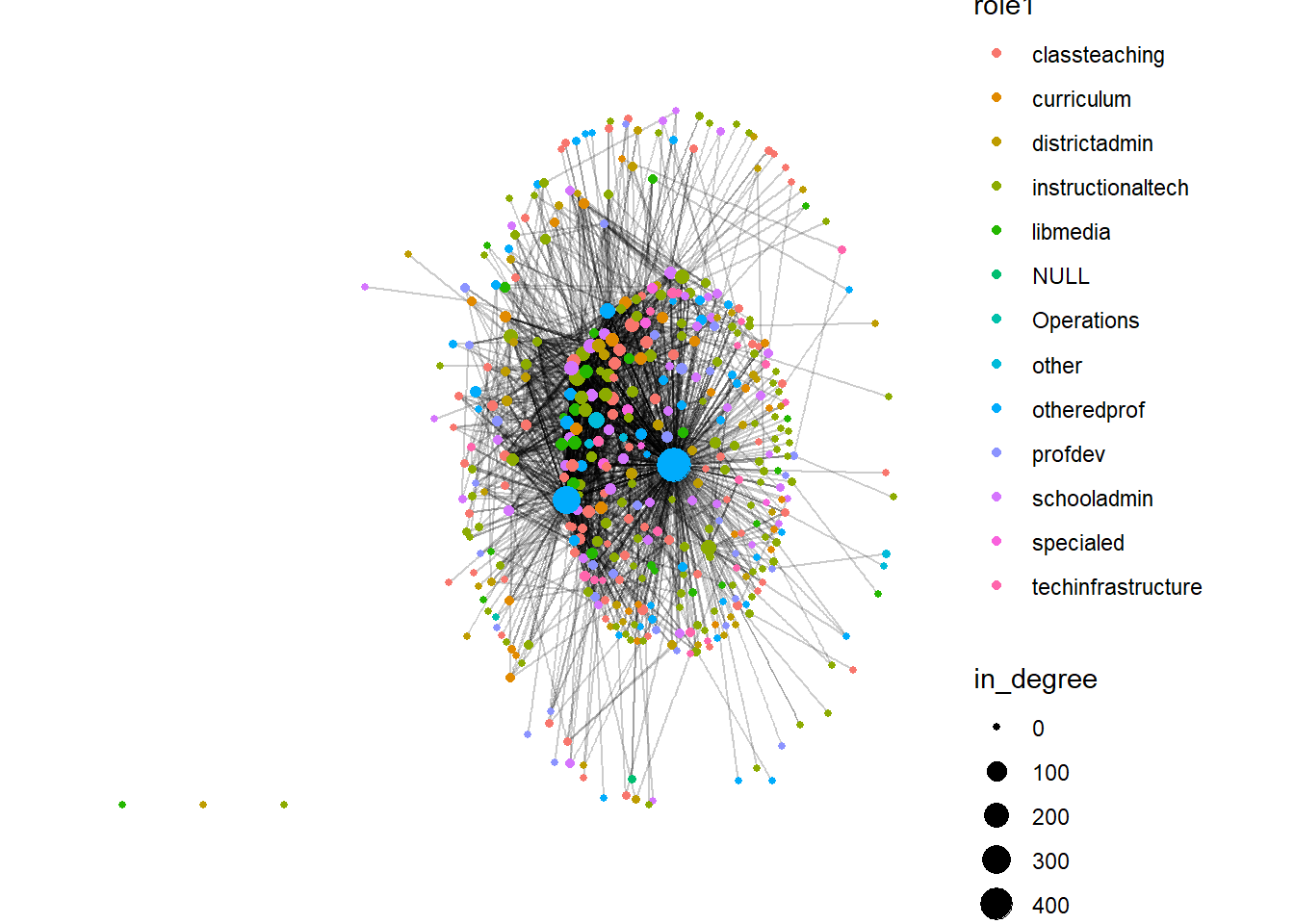

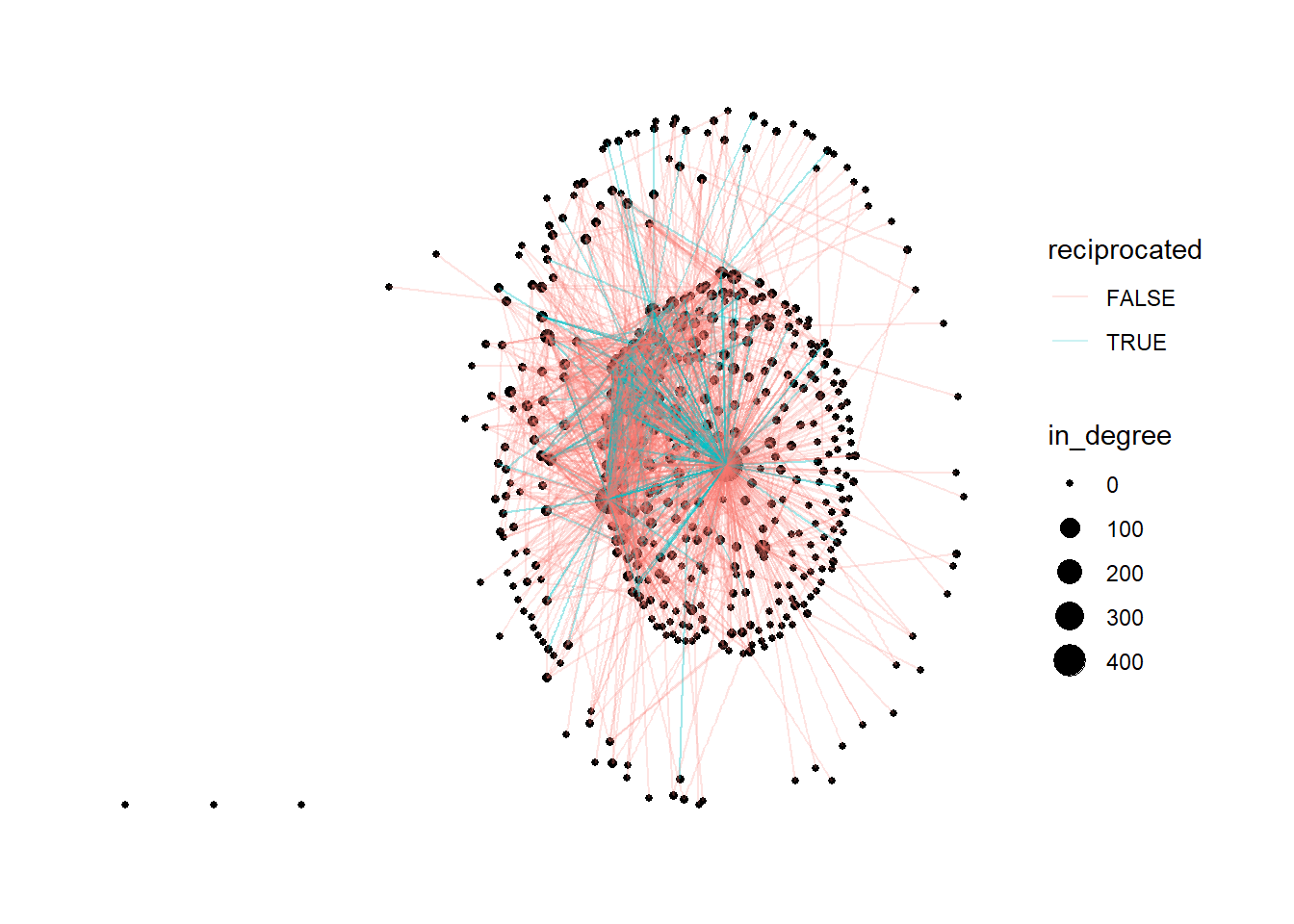

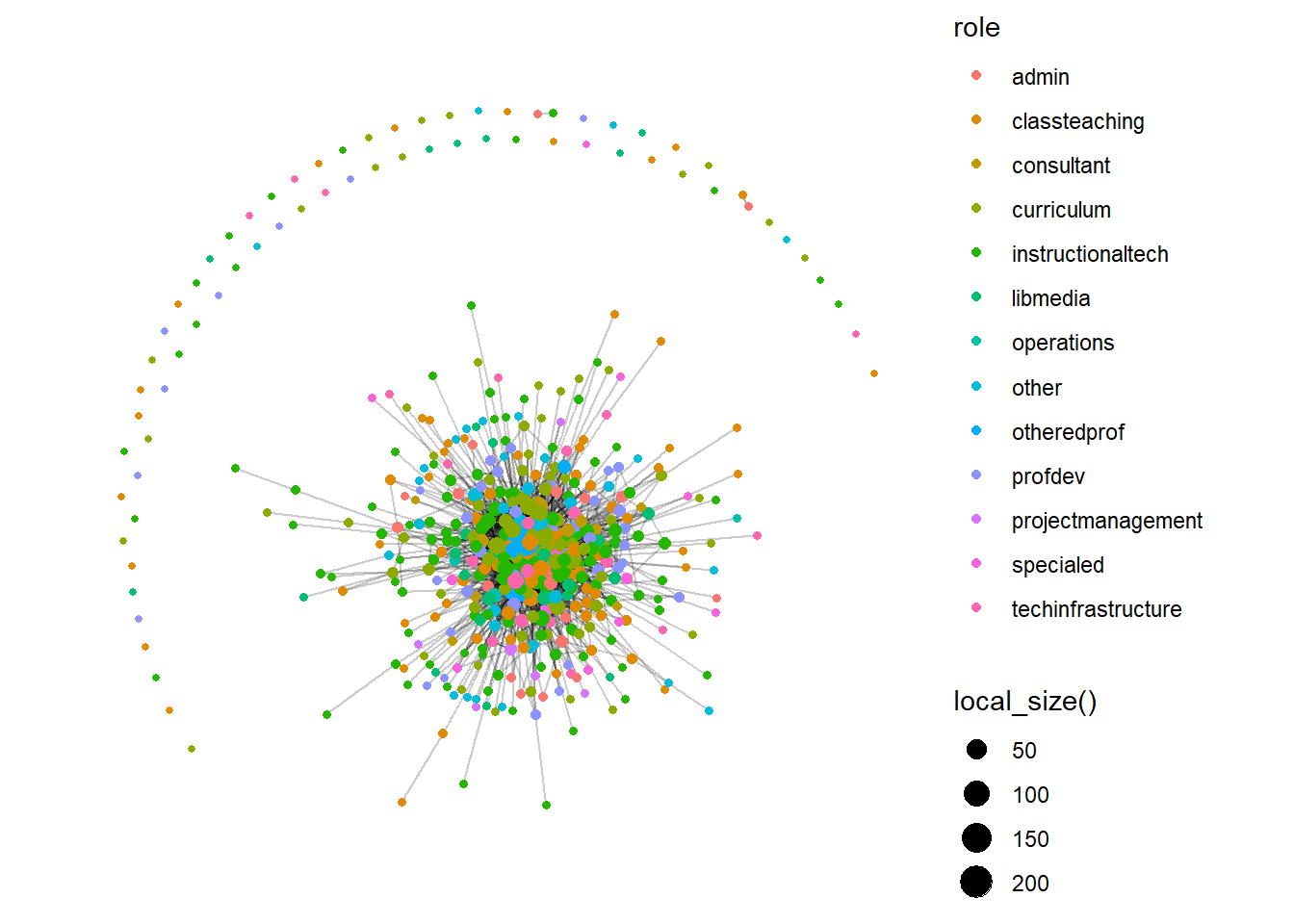

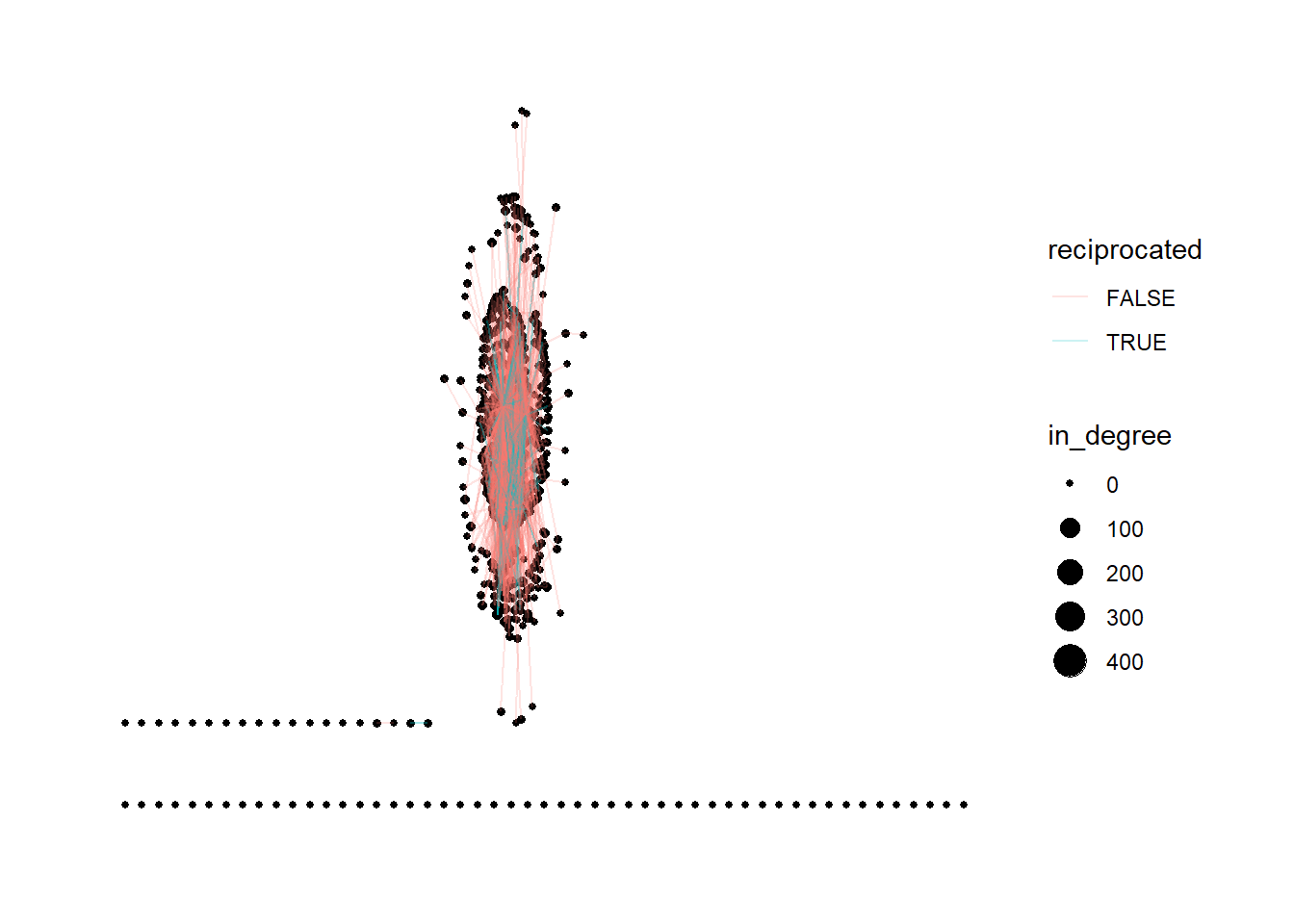

16 16 1Step 5: Egocentric Analysis – Centrality & Key Actors

ccss_network <- ccss_network |>

activate(nodes) |>

mutate(

size = local_size(),

in_degree = centrality_degree(mode = "in"),

out_degree = centrality_degree(mode = "out"),

closeness = centrality_closeness(),

betweenness = centrality_betweenness()

)

# Identify top actors by out_degree (transmitters), in_degree (transceivers), and both (transcenders)

top_transmitters <- ccss_network %>% as_tibble() %>% arrange(desc(out_degree)) %>% head(5)

top_transceivers <- ccss_network %>% as_tibble() %>% arrange(desc(in_degree)) %>% head(5)

top_transcenders <- ccss_network %>% as_tibble() %>%

filter(out_degree > quantile(out_degree, 0.9) & in_degree > quantile(in_degree, 0.9))Step 6: Visualize the Network

ggraph(ccss_network, layout = "fr") +

geom_node_point(aes(size = out_degree, color = out_degree)) +

geom_edge_link(alpha = .2) +

theme_graph()+

theme(text = element_text(family = "sans"))

Step 7: Sentiment Analysis (Optional)

If you want to analyze sentiment as in the original #COMMONCORE study:

library(vader)

vader_ccss <- vader_df(ccss_tweets$text)

mean(vader_ccss$compound)[1] 0.08668182 vader_ccss_summary <- vader_ccss %>%

mutate(sentiment = case_when(

compound >= 0.05 ~ "positive",

compound <= -0.05 ~ "negative",

TRUE ~ "neutral"

)) %>%

count(sentiment)4.4.4 Results and Discussion

RQ1: Who are the “transmitters,” “transceivers,” and “transcenders” in the Common Core Twitter network?

Transmitters (high out-degree):

The userSumayLustands out as the top transmitter, initiating 8 outgoing ties (mentions/retweets), followed byDouglasHolt...(5),WEquilSchool(3),fluttbot(3), andJoeWEquil(2). These users are the most active in broadcasting or mentioning others within the network.Transceivers (high in-degree):

The most-mentioned users areWEquilSchoolandSumayLu(in-degree = 3),JoeWEquil(2),Tech4Learni...(2), andLASER_Insti...(2). These individuals receive the most attention from other actors—potential focal points in conversations.Transcenders (high in-degree and out-degree):

Only two users—WEquilSchool(in-degree = 3, out-degree = 3) andSumayLu(in-degree = 3, out-degree = 8)—simultaneously act as hubs for both sending and receiving communication. These “bridging” actors may serve as key facilitators or connectors in the discourse.

RQ2: What subgroups or factions exist in the network?

- Component analysis shows a fragmented network:

- There are 14 weakly connected components, the largest containing 14 users, and several small groups or dyads (many with just 2–3 members).

- This fragmentation suggests limited overall cohesion, with multiple parallel or isolated conversations occurring.

- Clique analysis reveals:

- Four cliques (fully connected subgroups) of size 3 or 4—e.g., one 4-person clique involving nodes 3, 4, 5, and 6, and several overlapping 3-person cliques. This indicates pockets of tight-knit interaction, but such groups are rare relative to the size of the network.

- Community detection using edge betweenness identifies 16 subgroups, generally aligning with the component structure. The largest subgroup has 10 members, with most others much smaller.

RQ3: What is the overall sentiment in the network?

- VADER sentiment analysis of tweet content yields:

- An average sentiment score (

compound) of 0.09 (slightly positive), indicating that, despite the policy controversy, the sampled tweets were, on balance, more positive than negative. - When tweets are classified into categories:

- A mix of positive, neutral, and negative tweets is observed, with positive tweets slightly outnumbering negatives.

- This suggests the debate, at least in this time slice, included advocacy and constructive dialogue, not only criticism or negativity.

- An average sentiment score (

RQ4: What other patterns of communication (e.g., centrality, clique formation, isolates) characterize this network?

Centrality Patterns:

The network displays a classic “star” structure in its largest component. Two users,

SumayLuandWEquilSchool, stand out with high out-degree and in-degree centrality, respectively. Most other users have very low degree values (often 0 or 1), meaning they are peripheral, engaging in few interactions.- Transmitters (high out-degree): e.g.,

SumayLu(8 outgoing ties),DouglasHolt...(5). - Transceivers (high in-degree): e.g.,

WEquilSchool,SumayLu(both in-degree = 3). - Transcenders (both high in- and out-degree): rare—only

WEquilSchoolandSumayLumeet this criterion in this sample.

- Transmitters (high out-degree): e.g.,

Clique Formation:

Clique analysis revealed 4 cliques (fully connected subgroups) of size 3 or more, with one larger clique (size 4) and several overlapping smaller cliques. However, cliques are rare and limited in size—most communication occurs outside of dense subgroups.

Isolates and Components:

The network has 14 weak components—many of them tiny. Several users are isolates or part of isolated dyads and triads, meaning they are disconnected from the main conversation or only loosely connected. This points to a lack of broad, network-wide cohesion.

Community Structure:

Edge betweenness community detection found 16 subgroups, typically matching up with the component structure: most subgroups are very small (2–3 nodes), while the largest subgroup consists of 10 users.

Summary:

Communication in this network is characterized by:

- Strong centralization around a small number of users (hubs);

- Sparse and fragmented structure with many small, disconnected components;

- Limited clique formation—pockets of tightly connected users exist but are rare;

- Numerous isolates—users who are only weakly or not at all connected to the core discussion.

Discussion

This analysis of the Common Core Twitter conversation reveals a sparse and fragmented network structure. The debate is distributed across many small subgroups, with only one moderately sized component (14 members). Within this landscape:

- Key actors such as

SumayLuandWEquilSchoolserve as both broadcasters and focal points of attention (“transcenders”), but most users are peripheral, interacting minimally. - Cliques and communities are few and small, underscoring the lack of broad cohesion. Most interactions happen within micro-groups rather than across the entire network.

- Sentiment is, perhaps surprisingly, slightly positive on average. This may reflect the presence of advocacy groups, promotional messaging, or simply a lack of highly negative engagement during the observed period.

Implications:

The findings illustrate classic social network phenomena in online policy debate: - Most users are only lightly involved, and only a select few drive discussion or receive significant attention. - Communication is siloed, with many small isolated groups and minimal bridging between them. - Sentiment analysis offers nuance: while public debates may be assumed to be contentious, the prevailing tone can still be balanced or even positive in certain time slices.

For researchers and practitioners, this means that: - Identifying and engaging “transcenders” is essential for bridging subgroups and spreading information. - Interventions or outreach should consider the network’s fragmentation—broader influence may require engaging multiple small groups individually rather than targeting a single “core.” - Combining SNA with text/sentiment analysis gives a fuller picture: not just who is talking, but how and with what tone.

Future analysis could track changes in sentiment and connectivity over time, or compare subgroups for differences in message tone and network position.

References

- Supovitz, J., Daly, A.J., del Fresno, M., & Kolouch, C. (2017). #commoncore Project. Retrieved from http://www.hashtagcommoncore.com

- Carolan, B.V. (2014). Social Network Analysis and Education: Theory, Methods & Applications. Sage.

- Silge, J., & Robinson, D. (2017). Text Mining with R: A Tidy Approach. O’Reilly.